Episode Transcript

[00:00:01] Speaker A: This is another spontaneous episode of unraveling religion. My name is Joel Lessies. I'm the host, and I'm sitting here at before your quiet eyes in Rochester, New York, and I'm sitting with three dear friends, and I'm just wondering if we could start with David White. David, could you introduce yourself a little bit?

[00:00:19] Speaker B: My own biography is that went to Colgate University, a very old baptist college, and from there I proceeded to Cornell University for my PhD in philosophy. My first job was at the University of Lagos, and I was there for two years. I did my dissertation on. Bishop Butler was one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest of the anglican theologians. They were called divines, the great anglican divines. His work, especially the analogy religion, was very, very widely used in England, the US, and throughout the british empire.

Religion is practice. It's not thought, it's not assent to propositions.

And the practice should be reasonable, rational, it should be a good idea to do, but it doesn't have to be especially likely to succeed.

We often do things that will probably fail, but are still a good idea.

[00:01:44] Speaker A: Right.

[00:01:45] Speaker B: Attempting an ideal given the alternative.

[00:01:48] Speaker A: Ted, could you introduce yourself, and maybe you could introduce us to Plotinus.

[00:01:53] Speaker C: My name is Ted. I'm a retired electronics engineer. I specialized in designing control systems and communication systems. I'm the former editor of the bulletin of the Rochester Academy of Sciences.

I'm going to be the future editor of the Rochester Engineering Society.

[00:02:14] Speaker A: But, Ted, knowing you and I've been coming here for a while, you have a deep fascination with, what would you call it, like, religion, philosophy, existence. How would you frame that?

[00:02:24] Speaker C: I feel like we're alive, and I find that to be kind of a miraculous thing that we're alive. And not only that, but we're able to communicate to a certain extent with each other. And we can have thoughts and have memories and contemplate the future. For me, that's, like, shocking. When I was a little kid, when I was a little kid, I remember one day my mother took me to the zoo, buffalo Zoo, when they had a kitty, back in the day when they had a kitty petting section. And I remember I was in that stroller thing, and I stood up, I gripped the fence, and all of a sudden, I became aware of myself for the first time.

[00:03:06] Speaker A: Wow, that's very interesting.

[00:03:07] Speaker C: And that scared the fuck out of me.

[00:03:10] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:03:11] Speaker C: You're like three years old.

[00:03:13] Speaker A: A separate self.

[00:03:14] Speaker C: Yeah. And so I'm still in that state of shock, and I'm still trying to calm down from it.

[00:03:20] Speaker A: That makes a lot of sense. To me.

[00:03:22] Speaker C: Does it?

[00:03:22] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:03:23] Speaker D: I didn't know anybody else had a memory like that, that I was sitting there watching black and white television. Because that's early days of television. I go back that far and I suddenly said, I exist.

I suddenly realized, and I just said to myself, I exist.

[00:03:47] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:03:49] Speaker C: You can never tell. You're watching little kids what they're thinking.

[00:03:53] Speaker D: Right. Well, I'm Stephen, and mainly I'm a want. One day, hopefully, they'll say, he knew the poet Stephen Lloyd. Richard Burton said you knew the poet Dylan Thomas. Dylan wouldn't know anybody if he needed a fiver.

[00:04:11] Speaker A: Yeah, makes sense. I've seen you in the community. I lived here from 2017 to 2022, and I remember you from the poetic community. Yeah, I know. I've seen you at equal grounds. There's new ground poetry at equal grounds Cafe on South Avenue. I want to ask Ted to talk about Plotinus.

[00:04:33] Speaker C: Okay. Plotinus is sometimes called a neoplatonist, but he never considered himself that. He was a teacher of Plato. Platinus's key, I would say, number one nutshell standing on 1ft is that he was all about the soul. So what is the soul? What are the parts of the soul? What does the soul do? How do you increase your soul? What do you do to diminish your soul?

[00:04:59] Speaker A: That's a great question.

[00:05:00] Speaker C: So he thought everything had the soul. So, like, the universe has a soul. It's got a body and it's got a soul. The human beings have a body and a soul. So what is a soul?

There's different emphasis you could put on the soul. Like, my favorite one is the soul is the organ of being. That's a very cool frame for that.

You have this organ that recognizes other beings, including your own being.

[00:05:29] Speaker A: Right.

[00:05:30] Speaker C: And it's more than materiality. Sure. That book there has parts. There's four causes. In fact, right there is, like the material cause what a thing is made up of. There's the formal cause, which is what physics does. It shows you the blueprint of what is the theory behind it or what makes it work. There's the efficient cause, which is, okay, what caused this? What caused that? Like, this ball fell into the billiard pocket because this other ball hit it. But the most important one is ideological cause or the final cause. Everything has a purpose. For a thing to be a being, it needs to have a purpose. As know, the notion of a soul as an organ of being is, I think, a powerful one.

[00:06:16] Speaker A: That is very powerful.

[00:06:18] Speaker C: And that's why I love Plotinus.

[00:06:20] Speaker A: I can see why? Because as you just described him. That is very fascinating. I want to ask David in relation to Bishop Butler.

[00:06:27] Speaker B: Bishop Butler's sermons, 15 of them were published first collection of 1513, and 14 are on the love of God, and 15 is on ignorance.

[00:06:43] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:06:44] Speaker B: Butler, in his roles, sermons, sets up a trajectory that human nature, which he discusses in the earlier sermons. Yes, human nature has a tendency and affection that leads to the pursuit of the divine. If we have clarified our thoughts, it is divinity that will be most attractive to us.

But alas, we are ignorant of how to achieve the union that we desire and desire more than anything else that we might desire.

So Butler tries to sketch out, well, yes, we are pretty completely ignorant, but we do have a conscience which tells us in some way what's right to do.

We do have the intellect, which cannot give us complete knowledge, but can give us a probable knowledge.

[00:08:03] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:08:04] Speaker B: And we have an alleged revelation that we can try to read and interpret, get some guidance from. And we have institutions of church and state. Plotinus is, of course, much earlier for the english theologians, especially in the early 18th century, was what are we to do with the pre christian people, philosophers? And they seem to have been on the same basic trajectory, but they give.

[00:08:52] Speaker A: A view of what that trajectory is so that people, the audience, understands that post and pre, what we're talking about. That's the same thing, okay?

[00:09:01] Speaker B: In this world, we all have needs, and we fulfill those needs because we have desires, right? You need nutrition, but the only way you're going to get nutrition is if you have a desire for food and so on.

This world leads to great frustration, distraction, miscalculation. People do just insane things and live a whole life that is contrary to their self interest. Forget about morality and charity and their own nature. They violate their own nature.

The aspiration is to somehow get out of that misery and not get out of it with some phony baloney. Happiness of narcotics or entertainment. True happiness or true happiness? True fulfillment.

Whether this requires an immaterial existence, whether it requires a post mortem existence.

Speaking for myself, I would say those are open questions. Those are open questions.

From Butler's point of view, it doesn't matter that much as long as they're open questions, because this worldly path is the same. Whether you die and rot in the grave and that's it. Or whether you go on to whether there's something after doesn't matter that much. Because the path, he and the moral, the british moralists claim that the path in this world is the path of virtue, connects with it was also Plato's favorite word, Plato's virtue. Aristotle's virtue is a big favorite, and certainly with know.

[00:11:16] Speaker C: Plotinus.

[00:11:16] Speaker B: Yes, I completely agree. He's carrying on Platonism, but he also pays many tributes to Aristotle and to other. The dominant. The root metaphor is what is set out most beautifully in Plato's symposium, where you have to work through all of these different paths of ascent, and most importantly, you have to be open to instruction. So Butler had said when he was very young, he said that the business of his life was to seek the truth unashamed, to learn. Some of our strongest desires and passions are actually other regarding rather than self regarding. So in order to serve your own most narrow interest, you necessarily must act in a way that serves the interests of others.

[00:12:23] Speaker A: Just a sampling of different paths. The content of what those paths would look like, the initial paths like. What are we talking about when we're talking about paths for people?

What are the content? What are those paths? And not all of them, but just some of them. A sampling of that.

[00:12:40] Speaker C: Well, in Plato is just chock full of information on this particular topic to just pull two of them out of the hat. Yeah, he talks about virtue a lot.

[00:12:51] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:12:52] Speaker C: And he's got a famous dialogue where he explores what is virtue? And they go at it. Is it this? Is it that? Can it be taught?

[00:13:04] Speaker A: Is it intrinsic?

[00:13:05] Speaker C: Is it intrinsic?

Are you born with it? And the conclusion at the end of it is the same conclusion that almost all of his other dialogues. No. Virtue is ultimately divine of the divine nature. So you have to open yourself up to the divine to be either virtuous or truthful or any other virtue, if you want to call it that, and also makes it clear that the opposite of virtue is the same amartia, which means to miss the mark. Okay. Virtue is not just like a single direction. It's like you have to get it if you're too high, too low to left, to right.

[00:13:48] Speaker A: Sin is actually a metaphor of an archer whose arrow.

[00:13:52] Speaker C: That's right. Out of Plato. That's right out of Plato. The other thing I wanted to mention about Plato is he's got this allegory of the divided line and the divided line.

He divides everything into two parts. There's the world of matter, sensation, and then there's the mental world, things of the mind. And then he takes each of those two subdivisions and divides those two.

[00:14:17] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:14:18] Speaker C: So that at the lowest level, you have things like sensation, your body, the next level that's still within the physical realm he calls pistis, which is opinion.

[00:14:30] Speaker A: Okay?

[00:14:30] Speaker C: And it's not true knowledge. And then above that, now you're getting into the higher realm. You have something called dianoia, which is what we might call rationality, where you reason things out. That is like, you start out with assumptions, and then based on the assumptions or axioms, you deduce, using correct thinking, some conclusions. But that's not the highest state of mind. What is the highest state of mind, it's called is. It's what Plato is teaching people to do. Noises noesis is where you have to examine your assumptions and not just presume assumptions, that you have to examine everything and realize you don't know. You know what I mean? And ultimately, what you need, ultimately, it's a reorientation of yourself from the mundane towards the source, which is the divine. Now, in eastern Christianity, for them, salvation is about theosis.

[00:15:36] Speaker A: Okay?

[00:15:37] Speaker C: So step one is where you realize that there's something wrong. It's a recognition of evil or bad things or something incorrect, or you recognize that you're missing the mark.

So it's a withdrawal from the bad.

The second stage is to orient yourself towards the good and move in that direction. And the third final stage is like, in the allegory of the cave. It's like you now go and help someone else realize that they're doing wrong and there's a different path, and they need to go down this path. So it's kind of similar, but it's repackaged, so to speak.

[00:16:21] Speaker A: I just want to check in with David. Did you want to say anything about the paths?

[00:16:25] Speaker B: Yeah, I would. For Butler, there's one point of view of this world that you fit the different paths into this point of view.

The names that are used are test, trial, and probation.

[00:16:46] Speaker A: Okay. And this is the Bishop Butler framework.

[00:16:49] Speaker B: This is the Bishop Butler framework. Is that our business in this world is probationary. It is a practice. It is a test or a trial. And it's the kind of test of character that by taking the test, you improve your character. It's not just that you have the character separate. Now, if you say, well, what are the specific paths? You have to remember that not only was plotinus pre democratic, Butler was pre democratic. So what I attribute to Butler is going to be abrasive to modern people.

[00:17:40] Speaker A: Because when you define democratic for us.

[00:17:44] Speaker B: Everyone is equal with regard to right and the pursuit of happiness. In fact, Butler was a source for the American Declaration of Independence, the pursuit.

[00:17:55] Speaker A: Of happiness clause, the freedom of the individual. Is this what you're expressing?

[00:18:01] Speaker B: Yes, but I'm saying that from Butler's point of view, it was essentially what I would call a guild point of view, that within the world, there are these different guilds. And in order to advance, in order to be a better person, there's only one way, and that's to advance within a certain guild. And so you become a better printer, and by becoming a better printer, you become a better person. The aristocrats are. Yes, they're born with the silver spoon, but they are a sort of guild, and they have to do their aristocratic thing. And Butler, as a bishop, is repeatedly addressing the aristocrats and the wealthy, even who are commoners, and saying that this is not yours. This position that you hold is in trust. You hold it in trust.

[00:19:10] Speaker A: Well, it's a very interesting thing that you raise. Propriety. What is propriety in the world for human beings?

[00:19:15] Speaker B: What is that?

[00:19:16] Speaker A: That's a curious, very deep question.

[00:19:18] Speaker C: Yes.

[00:19:19] Speaker A: And if propriety both does and does not exist, in what ways does it not exist for a human being? This is the resignation of that I'm a vessel. I receive what I am given, and then I give it forward. But there is no actual propriety in what my experience.

[00:19:36] Speaker B: The sting in the tail of this is that if you adopt this point of view, this probationary, that you are a trustee.

[00:19:48] Speaker A: Yeah. What's the christian term for it? This realm is purgatory.

[00:19:53] Speaker B: Purgatory, absolutely, yes, purgatory. A purge.

A cleansing.

Okay, take all of that. And as I said, everybody encounters some frustration or annoyance or worse than that, every day.

You can look at it from two points of view. One is to whine and cry, why me? Oh, what a nuisance that I have to deal with this. And the other is, I'm on. I'm at bat.

I've got a job to do here. And as long as I address the situation to the best of my ability, then my character, my soul will advance, even if the outcome is unfortunate. On the other hand, and Plato would definitely back this up if I hit a home run. But by cheating, then I've gained nothing. The fact that they've posted the score is of no value or benefit at all.

[00:21:04] Speaker A: This leads me to the fundamental question that I want to pose for us, is process is important. And so this is what you're saying is that fundamentally, Plato was integrity of the process, ethical application of all facets of the process. And so my question is, let's talk about this now. Deconstructing virtue. Virtue in relation to the process. Right. I mean, this is just what we're talking about virtue in the relation to the process.

[00:21:34] Speaker C: Well, Plato and Fato, I think it is. It's all about virtue, if you're really into the topic of virtue.

[00:21:44] Speaker A: So if we're going to talk about virtue, let's ask the question. Let's begin here. What is virtue?

[00:21:50] Speaker C: Right. Well, to answer that question is to know what virtue is. But to know virtue is to be virtuous.

It's to act virtuously, which is the important thing. So how does one act virtuously?

[00:22:03] Speaker A: Right. It's the same question.

[00:22:04] Speaker C: Same question. It's just got a different dress on it.

In my reading of Plato and Platinus, it's not like, okay, there's a prearranged order that we need to fit into.

It's like there's a harmony. Everything is in harmony with everything else on all levels.

That's why Platonus talks about the various kinds of souls, universal soul, the smallest soul, is because everything is trying to be in harmony with each other. To be virtue is not the same as happiness. No, because the pursuit of happiness is not necessarily, although it could be the pursuit of virtue. Like, how many people will admit to trying to pursue virtue. I don't know. I've never run into any. There's no constitution of any government that says to help man pursue virtue.

[00:22:58] Speaker A: Why do you think that is? Why is virtue left out of the discourse? When you talk about governments of human.

[00:23:02] Speaker C: Beings, why doesn't the president have an annual speech where he declares the state of the virtue of the country?

[00:23:08] Speaker A: Do you think it's that our population, it's not in our paradigm. We're not taught and informed about virtue.

[00:23:17] Speaker B: Let's take your question.

Why doesn't the government, okay, when John Kennedy said, ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country. All we have to do to make that a lesson in virtue is to substitute for country, the whole world, and the person who acts on behalf of the good of all, the greatest good, the greatest benefit, is the person of virtue. Now, the promise in Christianity and the promise in platonism is that if you pursue a life of holding in trust, holding yourself in trust for the benefit of all, that you will end up being happy and being in the best state, the most desirable state for yourself. And of course, throughout history, there's been this running battle about the philosophers. I mean, everybody thinks it's a good idea, but the question is, how plausible is that self beneficial outcome? From Butler's point of view, when we talk about virtue, he says, look, come on, yes, there are some difficult, disputed cases, but almost all the time you know perfectly well. Almost all the time we know perfectly well, but we engage in self deception.

[00:25:01] Speaker C: That's only the first stage, is to recognize that something is not virtuous and to keep yourself from doing something obviously that's going to harm your virtue. That's only stage one. But a necessary stage is to help other people become virtuous. You can't be virtuous by yourself, like David is talking about the society at large. You can't be virtuous in isolation.

You can't use an excuse to force yourself to be unvirtuous. That's against the rules. So to have an excuse. Now, virtue is different than justice. Justice.

[00:25:37] Speaker A: Before you go on to how virtue differs from justice, I'm wondering what you said. There are three stages. Did you describe the application of how to become virtuous? Like the practical, what that looks like? Because it sounded like it said, don't do things harmful and help others to become virtuous. But I'm wondering, how do I become virtuous? What does that look like from a bishop butler or a platonist or Plato perspective?

[00:26:00] Speaker C: If you believe that there is other possible worlds, kind of like the man in the high castle kind of thing. If you have like these little tapes or books of possible worlds that are better than this one, then you start moving towards that.

But if you don't recognize the divine in some sense, there used to be virtue was dictated by the authorities of virtue. You had the papal magisterium, which determines what is and what is not truth and what is not virtue and all that. And then you had the Protestant Reformation, which tried to get rid of that and make everybody their own little ruler. So you decide in your heart or whatever nook and cranny, you keep it, what is good and what is bad.

[00:26:50] Speaker D: One of the problems is that virtue has a mystical quality that can't be defined, right?

[00:26:57] Speaker C: Because it's unknown.

[00:26:59] Speaker D: Well, like when Jesus says, virtue has gone out of me, you wouldn't imagine virtue itself. What is virtue becomes simply a mystical thing.

[00:27:10] Speaker A: You're saying Jesus said, it has gone out of me and my virtue has gone out of me and that he doesn't have strength, right?

[00:27:19] Speaker D: In a sense it could be. It could be these. Loss of strength is mojo.

There's a sense in which what's been lost is not defined because you wouldn't imagine that it would change the nature of Jesus. He wouldn't suddenly become a thief because he's lost virtue.

[00:27:38] Speaker B: I just think there's a much simpler way of putting human. If you want to call it virtue, you do something and then you go home, you sit down, you calm down, you ask yourself, well, how do I feel about what I did?

[00:27:56] Speaker A: Oh, I see. Upon reflection.

[00:27:59] Speaker B: Exactly. Reflection, right. We have as part of human nature an organ of reflection, which is conscience. And I need a second order reflection of. Is my reflection pure or is it contaminated with self deception?

[00:28:23] Speaker A: Right.

[00:28:24] Speaker B: And we all know the classic examples of people who seem to have succeeded in believing that they were right.

[00:28:36] Speaker A: Did you just say Donald Trump?

[00:28:38] Speaker B: Well, in Butler, it was not Donald Trump, actually. It was the people who killed King Charles I.

They thought they were doing the righteous thing. But Butler claims that they were self deceived and that they had put a cloak over their evil. He also dwells on the story of David and BathSheba, and how DaviD gets BAthSHebA's husband, Uriah, killed so that he can have Bathsheba to himself. And it's only when the prophet Nathan comes to him and presents an analogy that David, now that what he was doing was wrong.

[00:29:27] Speaker A: And I wanted to introduce this. There was a wonderful translation of the Tao de Jing. The Tao de Jing. The title, where does it come from? Tao. Well, Tao, we know, is the way. But what is the way? The way, as I understand it, is the sweet spot of this Pure spiritual and the pure physical, the sweet. The blending, like, beyond all agenda and ego. Self, the manifestation of action, as you would say, david, action in a human form, blending the cultivation in the physical through the spiritual. So it's the evolution, the way. Tao. The Tao is the way. It is formless. And yet here we are. But the second word is what I want to introduce to you, which I didn't know this, but Stephen Mitchell, in his translation of the Dao de Jing, sat trying to figure out the correct interpretation of.

And actually, the word that he arrived at is Virtue. It's the virTuous, the Way Virtue. Classic Qing is like a classic. And so Dei is virtue.

[00:30:33] Speaker B: Of course, an alternative translation that's very well known is power.

[00:30:36] Speaker A: Yeah, but I would say power is a poor translation because there isn't that the ethical or moral component.

[00:30:44] Speaker B: Every time virtue comes up, Judith tells her little joke about a woman of ill repute.

It's entertaining. I have no problem with her little joke, but she uses the joke to cut off the discussion.

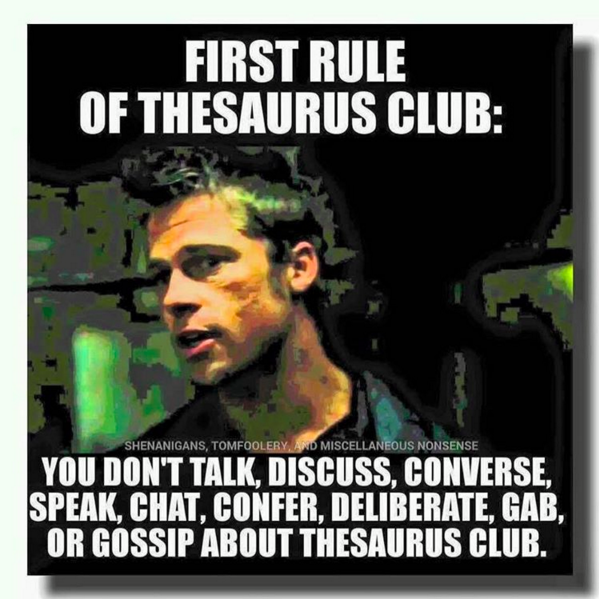

[00:31:03] Speaker A: I just came across this meme and I'll bring it to modern times, but I came across this meme that says people in the Sourus club don't talk about the source club. And then it goes on to list a whole litany of talk. Gab.

It goes on for like 15 words of talk about the source club. But if we're going to talk about virtue and she's going to sort of cut it off, what are some synonyms or other words that we could use in lieu of or to enhance our understanding of virtue? What's an good, good? Oh, I like that.

[00:31:38] Speaker C: Yeah. And daemon in Plato, Plato is always referring to as Damon.

[00:31:43] Speaker A: Yeah. What is that? Because I wanted to ask about that.

[00:31:46] Speaker C: It's like a spirit.

It's a spirit that evidently you're going about life and all of a sudden your daemon tells you. It gives you this feeling of dread or horror, that what you're doing is wrong. So there's this famous thing where they're talking about lysis's speech or something like that. And his daemon informs Plato. It doesn't give him anything positive, but it tells him that he's off the track, that this is not the right way. He's lost. He's lost Eros in particular. All right.

[00:32:22] Speaker A: What is the difference between daemon and intuition?

[00:32:25] Speaker C: Intuition is considered to be part of you. You have an intuition. Your daemon is not a part of you. It's not a part of you.

[00:32:32] Speaker A: Is it a non physical entity?

[00:32:34] Speaker C: Yes.

[00:32:34] Speaker A: Okay.

[00:32:35] Speaker C: One day Zeus decides he's going to create all these animals and things and trees and create the know. But then he tells up Ametheus. He gives them a big box of forms and he tells him, okay, you have to assign the forms to all these things that I'm creating. So Epimetheus decides, okay, go ahead. So Epimetheus gets this big bag of forms, that is, characteristics that his job is to assign to the animals. So to the tree, it's given long life and solidity. And to the bees, the ability to fly and to fertilize flowers, to the birds, to fly and sing, to the cheetah, to run quickly to the lion ferocity. And then it gets time to assign the form to the humans. And he looks in his bag and it's empty. The only thing that's left is an empty bag of characteristics.

[00:33:41] Speaker A: Yeah.

[00:33:42] Speaker C: So we're kind of stuck. We know that we're missing something, but it's up to us to continuously and never to our complete satisfaction decide what that like you're never going to be satisfied with what you find. So we're not a being, we're a becoming?

[00:34:01] Speaker A: Yes.

[00:34:03] Speaker C: Do you ever see the picture Michelangelo of the creation of Adam?

[00:34:08] Speaker A: Sure.

[00:34:08] Speaker C: I can't believe how many people don't get that picture.

[00:34:12] Speaker A: Tell us about it.

[00:34:13] Speaker C: Well, if you see the picture, there's like Adam laying there and he's got his hand up and then there's sort of God up there and he's got this cloak and there's all these beings underneath the cloak, God's finger and Adam's finger. And they interpret that as meaning God has just created man. And I know this fits in with Judaism as well. The creation of Adam is not in Adam, it's in that space between the fingers. It's God created a space for Adam. That's the creation giving him space. And that empty space is the creation, is what it is. That's the most important thing in that picture. People say, oh, that's just representational art. Every art, no matter how realistic looking or not realistic, is about something other than itself.

I have a friend of mine who's an art taught art, and he's very much into modern art and he's very opposed to representational art, and he thinks art should not be about something other than itself.

[00:35:17] Speaker A: Well, David has a poem.

[00:35:19] Speaker B: Oh, I do, yes.

[00:35:21] Speaker A: That's about modern art, is it not?

[00:35:23] Speaker B: It is, yes.

[00:35:24] Speaker A: What do you say about it? What is the title?

[00:35:27] Speaker B: Estrado. Abstract art does not refer to anything and therefore cannot mislead.

There is purity in abstract art since the only effect it has is its own. There is no associated object in abstract art, no practical considerations.

Abstraction is the mode of choice. For those concerned with the effect of art. Abstraction creates empathic bonding, passion to passion, member to member.

Thus the effect of the web of illusion, quotation, representation by the abstract and the counter abstract catalog, commonplace syllabi, archives, gallery, museum, studio, all aiming at the integrated field of being. But with preservatives of the past, even the deep past of the many mothers now so much in danger, with the social media eating away at the distinction between content and carrier.